FINAL REPORT on Commonalities and Differencies

Premise

The following Final Report “Greenwave in Vet Erasmus + Project” aims at underling and highlighting the commonalities and differencies across the EU partners’involved in the project.

This project aligns with the priorities of the new Erasmus+ program for environmental sustainability and UN objective 4.7, which aims to guarantee that all students acquire the knowledge and skills which are necessary to promote sustainable development as well as global citizenship.

The Green Wave VET project aims to explore and improve the integration of sustainable education in Professional and Technical Training (VET) contexts. Focusing on how the 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) can be implemented in construction and education sector, the project aims to develop a common pedagogical and didactic model for the development of the green skills. University of Bari in particular, focused on three main actions: (1) mapping existing educational approaches about sustainability in VET contexts and the analysis of emerging needs; (2) the understanding of how VET contexts promote sustainable education; (3) exploring ways to work effectively with the 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDG), especially in the construction building sectors.

First, these actions were aimed at identifying the best practices and understand the specific needs of different contexts in the education of sustainability; secondly develop an innovative pedagogicaldidactic model for the training of sustainability skills, which can be integrated within various methodologies: in particular these are Problems-Based Learning (PBL), Project Oriented Learning (POL) interwoven with the Emotional-Affective-Relational instances that intervene in the teachinglearning process, as is also verified by the most recent findings of affective neuroscience.

This model also bases its innovative character on one hand, stimulating the development of critical and creative-constructive skills to face the new challenges of sustainability always placing students at the center of learning process; on the other hand, offering an innovative pedagogical-didactic model for teachers, aimed not only at the creation of new contents relating to sustainability but also at the development, in a metacognitive sense, of the pre-conditions that allow us to think and build sustainability, for both poles of the educational relationship, students and teachers: in this model the Inner Development Goals (IDGs) are therefore addressed and developed, intended precisely as structural pre-conditions that futher allow the development of the skills of the Sustainable Development Goals.

The European partners involved in the project had the main objective to produce and create teaching materials, lessons, webinars, meetings and multiplier events to boost and foster the encompassing of SDGs and sustainability in their schools’curricula.

A final questionnaire to partners and teachers with interviews given to 16 students involved in the project were administered to evaluate the impact of the entire project on the communities

This Report is structured in 3 sections as follows:

Part I

GENERAL OVERVIEW:

research about sustainability, sustainability skills development and SDGs across the EU

Part II

PEDAGOGICAL-DIDACTIC MODEL THE CORE” OF GREENWAVE IN VET PROJECT.

Greenwave partners’ perceptions of commonalities and differencies, future perspectives about education on sustainability.

Part III

ENVISIONING THE FUTURE ABOUT SUSTAINABILITY:

teachers’s and students’ point of view on sustainability

The data for the completion of this report were drawn by:

- Greenwave partners’final questionnaire’s answers

- Teachers’ answers involved in the project – google module questionnaire-

- 16 students’interviews -2 students involved in the project given by each partner

Part I

General overview: research about sustainability, sustainability skills development and SDGs across the EU

The academic research that lies behind the project and the link with it is outlined in the following section.

1. Introduction

The current global landscape, marked by intricate and evolving challenges, underscores the urgent need for effective strategies and timely actions. This necessity is reinforced by the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), established in the 2030 Agenda, a significant advancement from Agenda 21. Central to this context are the Sustainable Development Goals, particularly Goal 4, which aims to ensure quality education, emphasizing the importance of Education for Sustainable Development (ESD) to promote sustainable lifestyles, human rights, gender equality, and other core values (Öhman, Sund, 2021).

Educational institutions, responding to these needs, are intensifying efforts to integrate ESD into their policies and curricula. The goal is to develop critical competencies such as systemic thinking, anticipatory and creative thinking, and strategic and action capabilities. These competencies are crucial for shaping individuals who can not only understand but also address and lead change towards sustainability (Tejedor et al., 2019).

Schools worldwide are responding to the challenge of incorporating sustainability into their educational policies through the adaptation of goals, content, and teaching methods (Öhman, Sund, 2021). Vare and Scott highlight the importance of viewing sustainable development as a process of social learning, focused on the ability to deal with dilemmas and contradictions. Scott argues that developing these abilities is a crucial objective for schools, contributing not only to social justice but also to human well-being (Öhman, Sund, 2021).

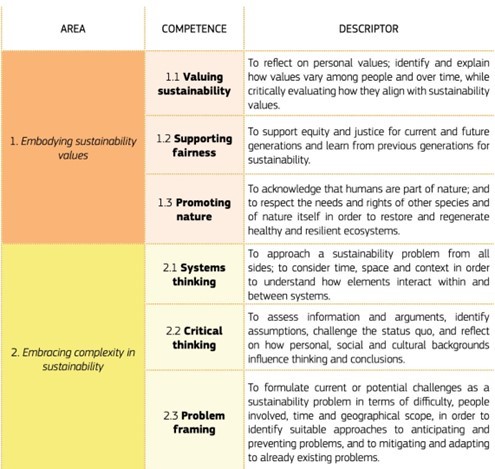

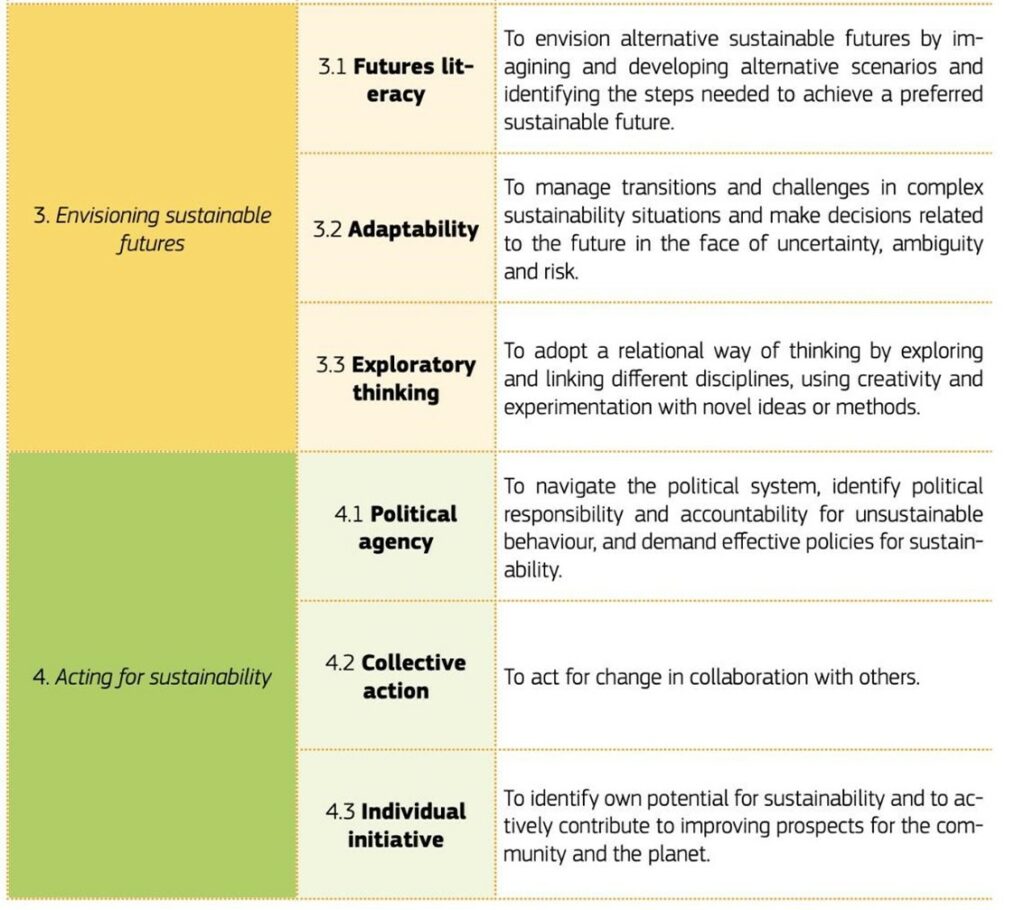

Competency-based education in sustainability can stimulate responsible action and motivate students to undertake or demand actions at local, national, and global levels. Developing sustainability competencies helps students overcome cognitive dissonance that arises from awareness of a problem but a lack of agency to address it. In this context, the GreenComp framework plays a critical role, aiding education and training systems in developing people accustomed to thinking systematically and critically, concerned about the present and future of our planet. The 12 competencies of the GreenComp framework are applicable to students of all ages and educational levels, in formal, nonformal, and informal educational contexts.

The UNESCO-UNEVOC document identifies several challenges in updating technical and vocational education and training (TVET) systems to align with the SDGs. These challenges include a lack of awareness about sustainability, outdated skills, and the need for greater engagement of key stakeholders (UNEVOC, 2021; UNEVOC, 2017).

To effectively implement the SDGs in vocational training institutions, UNESCO proposes a holistic approach that integrates sustainable development into the curriculum, research, community, and institutional culture (UNEVOC, 2017:12). It is essential for the TVET sector to align its programs and standards with current green skill needs and reflect these changes in pedagogical strategies (UNEVOC, 2017).

The transition towards a green economy, catalyzed by the COVID-19 pandemic, requires a radical renewal of development paradigms, emphasized by the European Union’s “Skills Agenda” of 2020. This transition anticipates that the shift to a low-carbon economy will open new job opportunities by 2030.

Finally, the Action Plan of the EU Agency Cedefop underscores the importance of green skills across all sectors, with a special emphasis on strategic areas like construction. This implies the need to develop skills in areas such as energy efficiency, renewable energies, circularity, and digitalization, recognizing the importance of such skills in promoting competitive sustainability and effectively responding to the environmental challenges of our time.

2. Sustainability Concept and Skill Development

As highlighted by the GreenComp report – European framework of competencies in sustainability (2022), sustainability (a broad and partly ambiguous concept) refers to a variety of meanings and applications depending on the context and the group of people involved. It is often confused with sustainable development, but while sustainability is a long-term goal for a more balanced world, sustainable development refers to the methods and processes to achieve this goal sustainably. Sustainability emphasizes the need to consider the needs of all forms of life and the planet itself, establishing a limit to human activities so as not to exceed the planet’s capacity.

In the educational field, there has been a significant shift towards integrating sustainable competencies into curricula. This movement is driven by the awareness that sustainability skills are crucial for shaping individuals capable of acting as agents of change towards a more sustainable future. These competencies include not just knowledge, but also the skills and attitudes necessary to understand and interact with complex systems, promoting actions that support the ecosystem and social justice.

The GreenComp framework plays a central role in this context, defining sustainability as a fundamental and cross-cutting competency at all ages. This competency is composed of various subelements aimed at developing the ability to think critically and systemically, planning and acting for sustainable futures. The approach to learning for environmental sustainability, part of this framework, aims to instill a sustainability-oriented mindset from childhood, preparing learners to become conscious and active change agents respecting the limits of our planet.

Below, we can observe the GreenComp areas, competences, and descriptors.

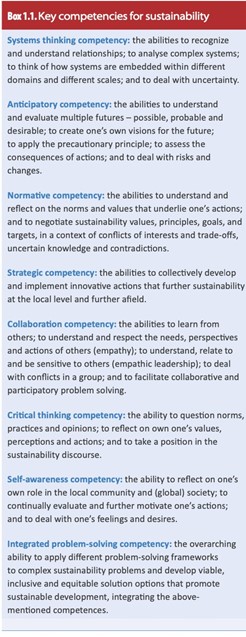

The UNESCO (2017) framework of key competences for sustainability is also fundamental for achieving the sustainable development goals of the 2030 Agenda and training people as “citizens of sustainability”. These skills represent transversal skills needed for all students of all ages around the world (developed at different age-appropriate levels). Key competences can be understood as transversal, multifunctional and context-independent and are considered crucial for promoting sustainable development (UNESCO, 2017, p.10). Sustainability core competencies represent what sustainability citizens particularly need to address today’s complex challenges.

3. Development of the Pedagogical-didactic model

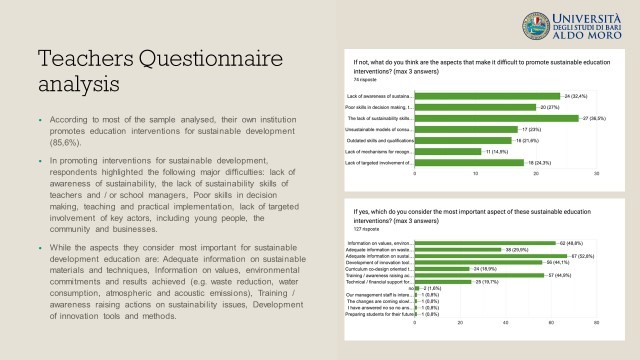

To develop the pedagogical-didactic model for sustainability we started from the analysis of the reports requested in the initial phase from the various partners and from the results and questionnaires administered to teachers and students of the VET institutes. Some key challenges emerged from the analysis:

- Difficulties in Legislation and Regulation Management: There is a discrepancy between national policies and strategies and European recommendations on sustainability. Furthermore, the presence of non-contextualized guidelines and resources that do not consider the specificities of the education and training systems of each country was noted.

- Need for Teacher Training: From the analysis of the questionnaires, a significant need for teacher training in the field of sustainable development emerged. There is little awareness of sustainability and a lack of practical skills in education for sustainable development. These gaps are reflected in the difficulty of integrating the goals of the 2030 Agenda into lessons and developing students’ green skills.

Some useful aspects for the definition of our model also emerged from an analysis of the literature. First, the need to make a distinction between key competences and action competences in the context of sustainability. The key competences, identified by UNESCO, are essential to train individuals capable of tackling sustainability challenges. However, competence orientation presents challenges, especially in their integration into teaching practice. In contrast, the concept of action competence emphasizes the development of critical thinking, dialogue and debate skills, and focuses on being qualified participants in sustainability issues (Öhman and Sund, 2021).

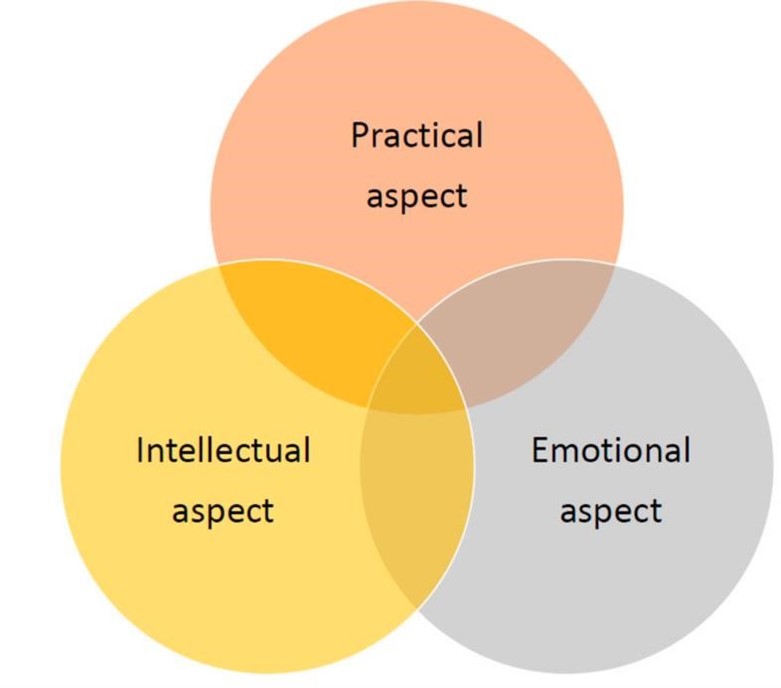

Hence the need to employ a multidimensional approach in learning, in fact according to Öhman and Sund (2021), to develop a solid commitment towards sustainability, it is important to offer students a variety of learning experiences that include intellectual, emotional and practical (Öhman and Sund, 2021, p.7):

- acquire knowledge on sustainability issues and relate (position yourself/locate yourself) with this knowledge (the intellectual aspect),

- articulate one’s emotional response and relate emotionally to sustainability issues (one’s ethical standards and beliefs) (the emotional aspect),

- develop one’s ability, motivation and desire to play an active role in finding democratic solutions to sustainability problems (the practical aspect).

Aspects of sustainability commitment. From Öhman and Sund, 202, p.8

These three fundamental aspects must be integrated into the pedagogical model for sustainability. This approach requires active methodologies that place the student at the center of the educational experience, facilitating the acquisition and development of knowledge, skills and competences necessary to act in a sustainable way. Such methodologies include problem solving, case studies, simulation, project-based learning, and service learning.

Recent studies indicate that better cognitive learning is achieved with community-oriented and constructive pedagogies that promote active and experiential learning. These educational practices increase cognitive learning about sustainability and incentivize interaction with stakeholders, favoring transdisciplinarity and stimulating systemic and critical thinking (Tejedor et al., 2019).

Frisk and Larson suggest the introduction of alternative forms of knowledge, such as procedural, effective, and social knowledge, to effectively educate for sustainability. They focus on skills such as systems thinking, long-term strategic reasoning, stakeholder engagement and team collaboration, as well as action orientation and the ability to act as change agents. Lambrechts and colleagues propose interactive and participatory, action-oriented and research methods as effective educational approaches for higher education for sustainable development (Tejedor et al., 2019).

Pedagogical strategies for sustainability, therefore, must be a set of procedures negotiated and applied in a reflective and flexible way, to promote teaching and learning that enhances understanding, emotion and practice in the education of students towards sustainability.

In conclusion, the pedagogical-didactic model for sustainability must incorporate these different elements and challenges, moving towards a holistic approach that takes into account key and action competences, and which promotes active and multidimensional learning to prepare students to be citizens aware and active in the field of sustainability.

Below we see the device.

1. Target audience

VET teachers and students

Contextualization and knowledge of the needs and levels of sustainability competence of teachers and students are necessary.

Usable tools:

-reports on policies, regulations and global frameworks related to sustainability;

-questionnaires for teachers and students in order to understand how VET contexts promote sustainable education and through which projects, actions and teaching strategies

2. Identification of skills and learning objectives

It is necessary to identify and integrate the eight key competences for UNESCO sustainability, including systemic thinking and collaborative competence, as well as the competences expressed by the European GreenComp framework within the curriculum.

Adopt the concept of action competence, focusing on developing the will, commitment and skills needed to address sustainability issues.

The learning objectives can be defined as follows:

- Develop the ability to critically analyze and contextualize knowledge, establishing connections between social, economic and environmental issues, both locally and globally. Students should be able to recognize and evaluate the interdependencies between various aspects of these issues, enhancing their critical and systemic thinking skills.

- Acquire practical skills for the sustainable use of resources, learning to minimize negative impacts on the natural and social environment. This objective should focus on the development of strategies and behaviors that promote resource conservation and ecological footprint reduction.

- Cultivate the ability to actively participate in community processes that support sustainability. Students should be encouraged to engage in local and global initiatives to promote sustainable practices, developing collaboration, communication and leadership skills.

- Integrate and apply the ethical principles linked to sustainability values in one’s personal and professional behavior. This objective aims to encourage students to reflect on the ethical implications of their actions and decisions, promoting a responsible and conscious approach both in daily life and in professional practice.

These learning objectives provide clear guidance for the incorporation of sustainability skills into educational programs, contributing to the formation of individuals who are aware, responsible and actively involved in promoting sustainable development.

3. Methodologies

We need to implement active methodologies that place students at the center of the educational process, such as problem solving, case studies and project-based learning.

Promote active experiential learning, enhancing cognitive learning about sustainability and stimulating critical and systemic thinking.

Summary of some methodologies:

- Problem-Based Learning, PBL, is a teaching strategy that places students, in small groups and under the supervision of a tutor, faced with the task of seeking and analyzing information to solve concrete problems. This approach not only promotes hypothesizing and identifying learning needs to better understand the problem, but also to achieve established learning objectives. In this context, solving the problem is not the main goal, but rather developing the ability to critically analyze information and data from different sources and learning from the solving process. PBL focuses on the development of cognitive, interpersonal and instrumental skills, useful for dealing with real situations close to professional practice. The main objective of PBL is to provide training that equips the future professional with tools and skills for intellectual problem solving. Distinctive features of PBL include: (1) emphasis on student responsibility for their own learning; (2) transdisciplinary or multidisciplinary nature of the problems; (3) inseparability between theory and practice; (4) focus on the process rather than the products obtained; (5) the role of the teacher moving from instructor to facilitator of learning; (6) focus on self- and peer-assessment rather than teacher-defined learning outcomes; and (7) emphasis on developing interpersonal and communication skills.

- Project-Oriented Learning, POL, also known as project-based learning, is a teaching method that has its roots in constructivism, developed by key figures such as Vygotsky, Bruner and Piaget. This approach is based on the idea that learning is built through the interaction between personal experiences and mental structures, allowing students to develop a network of mental structures that facilitate the creation of rational and meaningful relationships with the environment and society . In Project-Oriented Learning, students are placed at the center of the learning process, becoming the protagonists of their education. This method emphasizes student development through finding solutions to real, current problems, promoting an integrated and dynamic implementation of knowledge. Furthermore, this approach allows for a notable empowerment of students, as they are actively involved in their own learning path, contributing to greater motivation and involvement in the educational process.

- The case study is a teaching strategy that presents a real situation with one or more problems. The student must analyze the situation, propose solutions, answer questions and so on. This method promotes independent learning and can be done individually or in groups, offering different learning opportunities. The case study is based on real and significant situations from the student’s personal or professional point of view. The goal is to make the student reflect and develop an action plan to solve complex problems through multifactor analysis. It can range from a simple description of the problem to an in-depth investigation with documentation and research. Case studies can be combined with other strategies, such as problem-based learning or project-oriented learning, and are often used in alternative methodological approaches focused on self-study. Furthermore, they characterize cooperative learning, where the implementation is structured for the group of students. Key elements of a case study include: addressing real socio-environmental conflicts; the deepening of the interrelationships between various factors, contexts and entities; the analysis of the problem; the integration of disciplinary and metadisciplinary contents; and the promotion of critical reflection.

- Simulation, including role-playing and simulation games, is a teaching strategy that encourages experiential learning. Participants imitate an environment as realistically as possible, staging the spatial elements and characters involved. Fundamentally based on dramatization, simulation not only allows the expression of feelings and the representation of events, but also encourages personal reflection. This learning method strengthens communication skills, teamwork, and cognitive and metacognitive skills related to the topic covered. The simulation can be conducted in classrooms or other environments that offer a deeper sense of realism, allowing for a creative reproduction of reality that enhances individual or group contributions. Efficient in exploring complex socio-environmental conflicts, the simulation allows us to understand historical and procedural aspects and the role of the institutions and individuals involved. It is a useful tool for gaining a general understanding of problems and delving into social and educational issues, as well as preparing people to handle similar situations in reality. As highlighted by López Torres et al., simulation facilitates a holistic and transversal approach to sustainability issues, involving social, environmental, economic, political, educational and cultural aspects. Simulation practice allows to analyze complex systems and everyday interactions, offering a learning opportunity that goes beyond the capabilities of a traditional classroom. The main characteristics of a simulation include: (1) the approach to real socio-environmental conflicts; (2) the detailed analysis of the interrelationships between factors and contexts; (3) the critical analysis of problems, from identifying conflicts to creating solutions; (4) the integration of interdisciplinary content; and (5) the stimulation of critical awareness in participants. These methodologies can be integrated with video lessons, practical workshops, study visits and group projects.

4. The PEDAGOGICAL-DIDATIC MODEL

Based on these premises and conceptualizations the final “first version” of the PDM (Pedagogicaldidactic Model) was elaborated, shared with the partners, finalized and used by teachers and students involved in the project along with the teaching material built by the partners. The aim of the project result was to make a European model for how to proceed the SDG-implementation process depending on the present level. The result consisted of an illustration and an explaining text. The model needed to have a main focus at VET building and construction sector, but it was thought to be considered whether to use it in an even more generic way, profitable for all VET sectors. The final first version of it was as follows:

The path that led to this conceptual frame was double focused: on one hand it was intended to be, following the guidelines of the project, a practical tool for teachers to help them conceiving and incorporate the matter of sustainability in their curricular teachings; on the other hand it was thought as a development of philosophical inspirations given by different matrixes. These are John Dewey’s philosophical and pedagogical theories, the triadic pedagogical model of Intellectual-PracticalEmotional aspects for learning and EU Unesco-Unevoc key competences highlighted before, by framing all these knowledges within the variety of collaborative methodologies as shown. A scheme of the matrixes taken in consideration was as follows:

1. UNESCO 2017-UNEVOC KEY COMPETENCES

-GIVE VALUES-SUPPORTING THINKING FOR COMPLEXITY

-ENVISIONING ALTERNATIVE SUSTAINABLE FUTURES

-ACTION FOR SUSTAINABILITY:INDIVIDUAL, COLLECTIVE, POLITICAL LEVEL

2. SDGs-AGENDA 2030 TOPICS-TARGETS

3. DEWEY’S PHILOSOPHICAL HERITAGE focused on three main points:

– INTERPRET CHANGE

-INTEGRATE CHANGE AT SCHOOL

-RELATION SCHOOL-SOCIETY-LIFE

Particularly on J. Dewey’s thought was taken in consideration his sense of rebuilding the entire society through the school, therefore is conception about education as the key, mile stone for the social progress, seen as human progress first and foremost and for Democracy (Ibidem); being a pragmatist, idealist, strumentalist, neo-Idealist activist and behaviourist, his whole vision pointed a school as a Democratic school for an open and liberal society where the human being can flourish; therefore, mainly through the reading of J.Dewey’s work The School and Society, the centrality of the student in his/her personal inner development is fundamental leading his/her adulthood towards the concept of being a citizen that builds the society with democratic ideals. This is the reason why all the new conceptualization about the Inner Development Goals drawn our attention for the elaboration of the PD Model about sustainability skills development: the very personal and intimate sphere of each student as human being were to be addressed first in order to be able to develop sustainability skills, as will be showed further on.

The PD MODEL features required were asked by the project results as to be simple, clear, path giving, practical and compassing the three dimensions of learning (Intellectual, Practical, Emotional) as suggested by the EU Reports named as well as it was required to link related content to SDGs in VET contexts by underlining alternative materials, processes and products in the building construction sector.

With regard to the Intellectual aspect and competences that a teacher could think about while planning his/her lesson by using the PD Model, the leading path to the building of it was:

- Acquire knowledge on sustainability issues and relate with this knowledge –(based on key competences from Unesco)

- Content and metacognition: position yourself/locate yourself beteween Global and Local dimensions

- System thinking-Critical-Problem framing

DRIVING QUESTIONS FOR TEACHERS

- 1.How do you think this Global issue is related to your students’ local community?

- 2.What challenges do you think this Target could represent for your students?

- 3. How can your students formulate current or potential problems relating this Target with their own local community?

For the Emotional aspect:

– Articulate one’s emotional response and relate emotionally to sustainability issues (based on key competences from Unesco)

– Values and believes: one’s ethical standards and beliefs

– Valuing sustainabilitysupporting fairness

– Promoting nature

DRIVING QUESTIONS FOR TEACHERS

- 1. How could your students reflect on their personal values related to this Target?

- 2.How can your students learn about equity and justice around sustainability with this Topic?

- 3. How can your students relate this Target to an healthy and resilient ecosystem?

For the Practical aspect:

– Develop one’s ability, motivation and desire to play an active role in finding democratic solutions to sustainability problems –(based on key competences from Unesco)

– Acion planning

– Envisioning future: critically thinking, managing transitions,

– Envisioning alternative sustainable futures with others and act for change

DRIVING QUESTIONS FOR TEACHERS

- 1. How can your students be elicited by this Target to think about alternative solutions, considering risks as well in Vet context -materials,processes,products-?

- 2. How can you help your students, by linking different disciplines related to this Target, adopt a relational way of thinking and create new ideas?

- 3. How can your students think about demanding and promoting effective political action towards sustainability?

Let us now consider what is understood as a structural pre-condition to the development of sustainability skills as suggested by J. Dewey’s philosophical and pedagogical approach, also intended as a fundamental component of the building of the PD Model.

5. INNER DEVELOPMENT GOALS: an ontological pre-condition for the development of sustainability skills

Another feature and critical matrix was taken into consideration for the development of the PD Model: the so called Inner development goals (www.innerdevelopmentgoals.org)

What do we mean by Inner Development, why and how this concept is related and relevant for the development of sustainability skills?

We need to start by defining what is intended as educational poverty (Botezat, A. 2016): to identifying and evaluate the educational poverty, Istat has indicated the educational poverty index as a parameter which is established through four dimensions:

1. Participation; 2. Resilience; 3. The ability to establish new relationships; 4. The standard of living.

Focusing on the ability to establish new relationships, it is possible to state that it is characterized by the ability of problem solving, communication, prosocial attitudes, whose task is to act as promoters in intra- and interpersonal relationships. Therefore, the importance of the school institution is revealed, understood as that body capable of providing adequate care and attention to relationality, both in the sense of learnability and teachability (Damiano, 2021). The function of the education system, therefore, appears to be of fundamental importance for the promotion and development of basic skills, and consequently, for the correct functioning of the student and the future citizen in society (Rosa, 2015). In this regard, the teacher’s task is to continually ask herself/himself the question previously described in order to try to remove the obstacles that can affect the four sub-dimensions depicted. The importance of continually investing in culture and education is evident, which in other words is equivalent to being able to build a winning future from the point of view of social living skills and other people’s recognition (Bilégué, 2019). We therefore recognize the individuality and specialty of each one and an interrelated and interconnected system in which each represents an element we can interact with and therefore create an evolution in progress. In this context, the role of the teaching-learning process is constantly reorganizing and restructuring, and it is for this reason that it is important to establish the foundations of an educational perspective open to the challenges of society and knowledge (Perla, Vinci, 2021). It is from this perspective that we believe, in light of some reflections that we will make, that learning develops as a consequence of relationality, in turn as a consequence of affectivity. The teacher, therefore, should consider the development of Inner structures also when thinking about developing the concept of sustainability: with regard to the principles of the Inner development as it is addressed in the framework of the Inner Development Goals (IDG) we refer to the background and method highlited in the Transformational skills for Sustainable Development (www.innerdevelopmentgoals.org).

The report of Thomas Jordan is focused on the account of the first phase of Inner Development Goals project that gathered researchers, CEOs, HR managers, sustainability managers and leaders of the Swedish academic institutions such as The Stockholm School of Economics, the Center for Social Sustainability at Karolinska Institutet, the Lund University Centre for Sustainability Studies and Stockholm University. During 2020 a series of five consultative meetings were held within a network comprising about 80 managers, researchers and organizational consultants discussing particularly the general frame of the project and the survey design: two surveys were made, the first one launched on the 1st March 2021 and the 2nd on the 19th April.

The aim of the surveys -as well as the entire project- was to identify skills and qualities felt as essential to further develop the competences needed to accomplish the UN SDGs: the main idea was to build “an inventory of what such crucial abilities, qualities and skills are perceived to be and create a framework that clearly articulates these in ways we can reach a high level of agreement about” (Inner Deveopment Goals report, pag. 5); the starting point of the whole vision about the project was a common belief that “there is a blind spot in our efforts to create a sustainable global society” (Ibidem) since although we accumulated much knowledge about environmental problems, climate change, poverty, public health etc., and so we know a lot about causes and factors that realized the actual situation of the planet, we still are not clear about what skills and personal qualities of the single individuals, as well as collective communities, need to be acquired in order to make the change highlighted by UN SDGs. So, the initiators of the IDG project were motivated by the belief that what was missing on the part of education was a “keen insight into what abilities, qualities or skills we need to foster among those individuals, groups and organizations that play crucial roles in working to fulfill the visions” (ibi). Therefore, what was on theme in this shared vision was the urgency to find the ontological pre-condition that allows the sustainability skills to be developed.

In fact “The argument is that we talk far more about what ought to be done to resolve the problems out in the world, than we talk about how to build skillfulness among the actors who are in a position to make the vision happen” (ibidem, pag. 3) and so the purpose of the IDG initiative was to draw attention to the need to support development of abilities, skills and inner qualities: building a framework that describes these qualities was the first achievement of the project.

A draft of IDG framework was presented and discussed at the workshop on 28 April with about 150 participants, in 12 May at the MindShift conference at SSE with 1.500 participants and also in May 29th at the Integral European Conference; secondly, as said, two surveys were then designed to outline which skills and qualities were seen as relevant in order to work more effectively towards the SDGs, formulated in the following way:

- What abilities, qualities or skills do you believe are essential to develop, individually and collectively, in order to get us significantly closer to fulfilling the UN SDGs?

- In the following text boxex, please write 3-7 abilities, qualities or skills and add, if you want, a brief comment on why you feel these abilities, qualities or skills are essential.

-The design and the description of participants, with methods, analysis of the responses and general outcomes of the surveys are outlined in the report, mainly carried out by T. Jordan and M. Booth (Ibidem, pag.8)-

So, what was important for the final elaboration of the PD Model of the Greenwave Vet project was to encompass these findings in it; the most important trait and focus of the all project was the identification of the main categories of qualities and skills that are related to what we call Inner Development intended as the pre-condition of Sustainability: different skills and qualities included in the IDG framework are often overlapping and interdependent, some are more fundamental and prerequisites for others, but a part of this what is relevant is the intention of leaving the framework on one side defined but on the other side also open; the focus is that the IDG framework could be seen as a useful pedagogical framework (Ibidem, pag. 12). A full and analytic deepening of all the 23 skills and qualities are in the report.

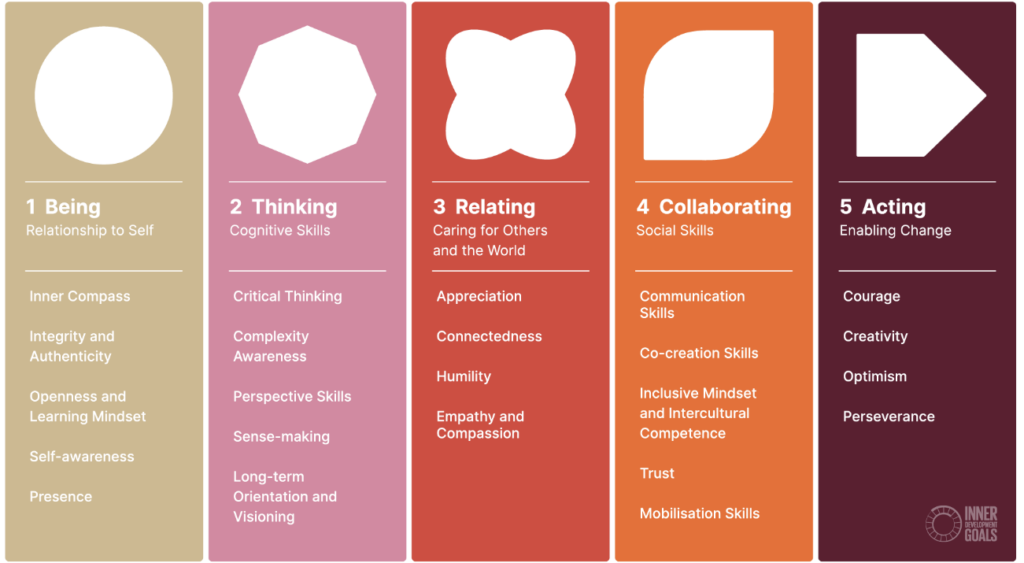

Table- Overview of the Inner Development Goals framework

| BEING Relationship to self | THINKING Cognitive skills | RELATING Caring for others and the world | COLLABORATING Social skills | ACTING Driving change |

| Inner compass | Critical thinking | Appreciation | Communication skills | Courage |

| Integrity and authenticity | Complexity awareness | Connectedness | Co-creation skills | Creativity |

| Openness and Learning mindset | Perspective skills | Humility | Inclusive mindset and intercultural competence | Optimism |

| Self-awareness | Sense-making | Empathy and compassion | Trust | Perseverance |

| Presence | Long-term orientation and visioning | Mobilization skills |

This is what we did about the IDG framework: a pedagogical tool that led us to the elaboration of our pedagogical-didactic model for Greenwave Vet project, in particularly the elaboration of the grid helped us to identify the leading questions for teachers that they had to ask as a guide for the elaboration of the lessons –as shown in the graph of PDM-.

6. Evaluation

To assess effectively, it is crucial to consider how integrated, coherent and contextualized student knowledge is. Formative assessment is fundamental, allowing teachers to monitor learning in real time.

Formative assessment, through constant feedback, becomes an essential guide for assessment in the twenty-first century. This methodology is effective for clarifying learning objectives, ensuring continuous monitoring, providing feedback, responding to student progress, encouraging adaptation and improvement of learning outcomes, and engaging students in a process of self- and peerassessment.

Formative assessments are crucial for identifying and correcting learning gaps, avoiding profound misunderstandings or misapplications of skills. Tools like rubrics become essential in 21st century classrooms, offering teachers and students clear guidelines for defining acceptable performance levels.

It is also important to teach students to evaluate their own learning, helping them to master content and improve their metacognitive skills. This includes learning how to learn and reflecting on your own learning process. This approach helps students become more aware and autonomous in their educational journey (Scott, 2015).

The final two tasks of the project –which are still ongoing- are Task 5 and 6: “Task 5 Plan and conduct an evaluation with VET students, who have been “the target” for the new materials/methods. Task 6: Make a second and final version of the model, based on the sayings from the students, the teachers and the managers”. (Project result details 2, Greenwave in Vet Project 2022).

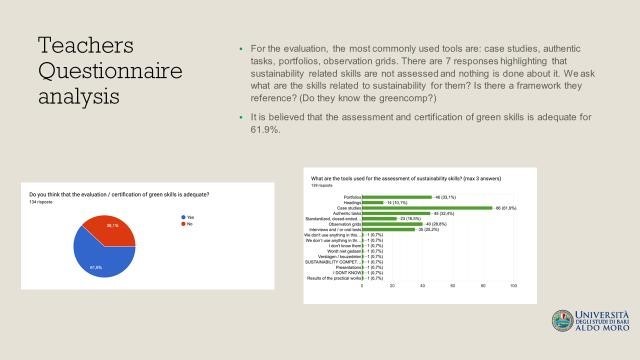

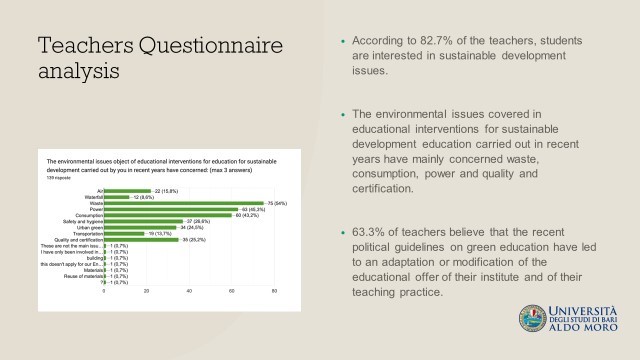

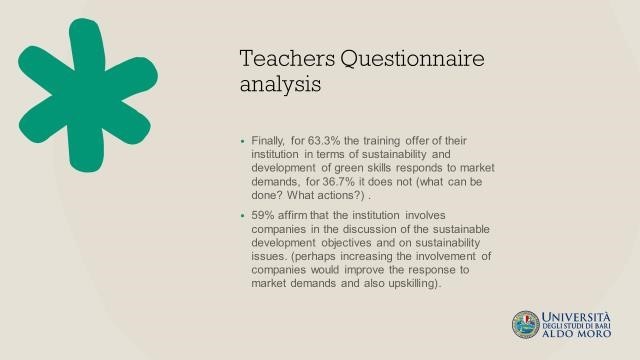

For the final evaluation also in order to accomplish the final tasks of the project the following tools were used:

-partners’ questionnaire

-teachers’ questionnaire

-students’ interviews

Questions for Greenwavers’partners as follows in the next Second Part of this Report to gather and evaluate the impact of the educational intervention on the whole project also aimed at developing and strengthening skills for sustainability in European Vet contexts.

7. Conclusions

The whole Greenwave Vet Erasmus project has shown the potentialities hidden in the teaching sustainability for both teachers and students: by insisting on and encompassing all the different key competences shown in the various EU Reports named in subjects curriculum with also the underlining of the Inner Development Goals, it is clear to what extend is possible to strengthen the skills required for the change we are aiming for the sustainability and the life on our planet.

This project has given a strong reinforcement to the idea that also the Teacher Education requires a deep thinking about pedagogy and didactics around sustainability: by conducting an initial survey to both teachers and students across the European countries involved in the project aimed at identifying the educational needs around sustainability and subsequently building the Pedagogical-didactic model with which constructing the lessons it has been clear that:

- There is a need to fill the gap across the subjects and the teaching sustainability

- It is possible to create a link between all disciplines and the core of sustainability

- The Teacher Education of all EU countries involved in the project needs and welcomes a common Pedagogical-didactic Model to share in order to help teachers to plan their lessons about sustainability

- There is a pre-condition that helps thinking, strengthening and acting for the sustainability which regard the Inner development skills of all human beings

To conclude with, a greater emphasis should be given to the Teacher Education across the EU countries by training teachers especially to the link between sustainability issues, curricular subjects and Inner Development Goals.

References

Bianchi, G., Pisiotis, U. and Cabrera Giraldez, M., GreenComp The European sustainability competence framework, Punie, Y. and Bacigalupo, M. editor(s), EUR 30955 EN, Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg, 2022, ISBN 978-92-76-53201-9, doi:10.2760/821058, JRC128040.

Bilégué, A. R. (2019). Educating today: a philosophical reflection starting from Edith Stein. Dialegesthai, 21.

Botezat, A. (2016). Educational poverty. NESET (Network of Experts working on the Social Dimension of Education and Training) II ad hoc question, (5)

Cynthia Luna Scott. THE FUTURES of LEARNING 3: What kind of pedagogies for the 21st century? UNESCO Education Research and Foresight, Paris. [ERF Working Papers Series, No. 15].

Dewey, J., The School and Society, Chicago, The University Chicago Press, 1915

Gemma Tejedor, Jordi Segalàs, Ángela Barrón, Mónica Fernández-Morilla, M. Teresa Fuertes, Jorge Ruiz-Morales, Ibón Gutiérrez, Esther García-González, Pilar Aramburuzabala, Àngels Hernández, (2019). Didactic Strategies to Promote Competencies in Sustainability, Sustainability 2019, 11, 2086; doi:10.3390/su11072086

Immordino-Yang, M. H., & Gotlieb, R. (2017). Embodied brains, social minds, cultural meaning: Integrating neuroscientific and educational research on social-affective development. American Educational Research Journal, 54(1_suppl), 344S-367S.

Mortari, L. (2009). Research and reflect. The training of the professional teacher. Carocci.

Natalini, A. (2022). Emotions, learning processes and emotional culture. PHILOSOPHERS (AND) SEMIOTICS, 9, 72-82.

Öhman,J.;Sund,L.A Didactic Model of Sustainability Commitment. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3083.

https://doi.org/10.3390/ su13063083

Perla, L., & Vinci, V. (2021). Teaching, professional recognition and innovation in universities. Teaching, professional recognition and innovation in universities, 1- 479.

Panksepp, J. (2016). The psycho-neurology of cross-species affective/social neuroscience:

Understanding animal affective states as a guide to development of novel psychiatric treatments. In Social Behavior from Rodents to Humans: Neural Foundations and Clinical Implications (pp. 109125). Cham: Springer International Publishing.

Rovatti, F. (2020). The role of mirror neurons in empathy. Training & Teaching, 18(4), 35-42. Sang, G. (2020). Teacher agency. Encyclopedia of teacher education, 1-5.

Scalcione, V. N. (2022). Skills and evaluation: the planning of educational action. Skills and evaluation: the planning of educational action, 201-230.

Scarinci, A., & Dipace, A. (2021). Methodological training, teaching technologies and experiences in promoting teaching and learning skills. Methodological training, educational technologies and experiences in promoting teaching and learning skills, 95-111.

Serbati, A. (2019). How to define student learning goals: from educational objectives to skills and Learning Outcomes. In Teaching at University. Methods and tools for effective teaching (pp. 37-56). Franco Angeli.

Tore, R., & Peretti, D. (2020). Train academics in the use of formative, constructive, transformative assessment of learning. Form@re, 20(1).

Travaglini, R. (2021). Game pedagogy and education. Development, learning, creativity (Vol. 1108, pp. 1-144). Franco Angeli.

UNESCO. Education for Sustainable Development Goals Learning Objectives; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2017. Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000247444

Vygotsky, L. S. (1969). Learning and intellectual development in school age. Vygotsky, L.S., et al. Psychology and Pedagogy, cit. in this bibliography.

Zanetti, M. A., Gualdi, G., & Francesca, Z. (2017). Academic success and transversal skills: what relationship?. In Congress Proceedings.

Zhang, L., Basham, J. D., & Yang, S. (2020). Understanding the implementation of personalized learning: A research synthesis. Educational Research Review, 31, 100339.

Weil, S. (2019). Universal Declaration of Human Rights. Garzanti.

PART II

“THE CORE” OF GREENWAVE IN VET PROJECT: EDUCATION.

Greenwave partners’ perceptions of commonalities and differencies, future perspectives about education on sustainability.

The following questions were submitted to each partner to gather their perceptions about the entire project, what were felt as commonalities and differencies among the countries, what was felt about sustainability education in the future after the Greenwave experience.

To start with, the following guidelines had been given to the partners to grasp the general perceptions of all the people involved in the project (named as GREENWAVE PARTNERS)

Please answer these questions (also giving a brief summary of your notes during the TPM in Randers) to describe your thoughts and feelings about the “Greenwave project”

We want to evaluate the general impact of the project to each one of us, in terms of personal growth and to our school

–What is your general perception about how the issue and teaching of sustainability is felt in your school and in your country?

-What do you think are the technical commonalities/differences among the EU countries in the field of sustainable building construction?

-What are your considerations about the teaching materials created, webinars and meetings held during the project in terms of educational impact?

-To what extend the “Greenwave in Vet project” has inspired you about teaching sustainability?

– Which impact do you think the “Greenwave in Vet project” will have in the next future at your school?

All the people involved in the project gave their answers outiling their perceptions about commonalities and differencies among the European countries as well as their opinions based on the Greenwave experience about the future of sustainability in Vet context.

CONSIDERATIONS FROM THE GREENWAVE IN VET PARTNERS: COMMONALITIES AND DIFFERENCIES ACROSS EU ABOUT EDUCATION ON SUSTAINABILITY

It could be definetly said that this project made a big difference about the general perceptions and overview about sustainability compared to the previous considerations that all the people involved in the project as partners of Greenwave in Vet had before the same project: the raising of awareness on the personal level of the people/professionals involevd in the project about the issue of sustainability through webinars, activities, events and materials generated by the Greenwave project was felt as the biggest achievement; even people coming from Netherlands, which is felt to be ahead as country about all aspects about sustainability in comparison with the other EU countries, reported a feeling of improvement in the knowledge and awareness on sustainability in general.

Thanks to the project, generally speaking for all the people who worked on Greenwave it became clear such a distinction between the southern European countries and the northern European countries: the knowledge of sustainable solutions in building-construction schools is on the table Spain and Italy, but using these solutions and developing the construction sector is happening faster in Netherlands and secondly in Denmark than in Spain and Italy. This is perceived as a result of culture, national policy and national financial situation.

Even when people reported a strong impact that the project had on their personal knowledge about sustainability issues and education, for some sustainability is felt to be still in its infancy: from Denmark which is making steps forward to it, the subject seems to not really appeal to young people yet. This sometimes is perceived as a difficulty to properly implement this within the lessons at school.

Some of the persons involved in the project said: “I don’t think the project has had any specific effects on the school, but the project has helped to push students and teachers’ mindset about sustainability

During the project the partners generally reported to have discovered that the Netherlands and Denmark have major similarities when we talk about sustainability: the reasons for that are felt to lie in things such as equality in climate, education system, residents and institution.

A great example about sustainability in all aspects, was perceived from all the partners, to be Netherlands: moving from the general perceptions to the core of the project and so the education on sustainability, Netherlands is implementing the SDG’s in the school curricula and lessons for many years. Strong and vivid icon for all the other countries.

Given this what was strucking about the project was that even for Netherlands Greenwave was a fantastic, enthusiastic new source of inspiration and improvement for education on sustainability:

“About learning during the project, I can say I learnt a lot. Hands, head, heart is an old concept but good it became important again.

The link with the SDG’s was a great new insight.

The toolkits for the implementation in the school, departments and lessons was new.

The webinars were great.

The learning activities were put into a nice frame.

The relation in between all SDG’s and building and construction was clarified (for the first time)”

On the same line Italy state: “The work carried out over the last two years through meetings and developing shared teaching models in terms of environmental sustainability and the webinars created have had an important impact. They have created moments of reflection for our teachers and students. in particular, the webinars proposed reflections on materials and construction techniques and led us to reflect on how much work still needs to be done to have sustainable cities, and on what we should improve in terms of environmental impact. The project aims to create a green mentality and through all the various steps of the project faced from time to time we have certainly sown the green mentality”.

The relationships created by the Greenwave project between partners generated a new force and source of contents and methods to offer for the implementation of teaching sustainability across Europe: this could be said to be a relevant and full of inspiration and hope for the entire teaching.

As a common and shared vision about the efficacy of the project could be reported as such: “I believe the project has helped us to see clearly what our next development should be. In the project there is a lot of fine materials to implement in our teaching and training right now – this is good, but the biggest impact is, that we now have an idea about what our next steps should be as a school – also broader than VET and building and construction. In three to four years the SDGs will be visible in our school as a whole. In our teaching and training, in our strategy and in our school environment.

Inspired by our Dutch partners we will include our school board in this process.”

Differencies and new insights across the Eu

Indeed, a whole new module called Green wave in VET has been created in the school from Netherlands as well as videos in which teachers explain how all their courses are paying attention to sustainability: giving new ideas about teaching as well as hints on the facility management was a very goos additional value for the school thanks to the project.

On the same line, new improvements came as a source of inspiration from the imputs given by the project such as “I think that we as a school should take some more steps, for example waste collection and reuse of furniture and/or equipment.”

Another common opinion shared by the partners with regard to take Netherlands as a virtuous example on sustainability was the building of the school partner: “our sustainable building shows that we walk the talk” has been said and this aspect had a great impact on the participants coming from the other countries.

The differencies between the European countries involved in the project was felt also by Denmark:

highlighting the “how” the build and construct process taks place, the schools are felt to be very different, with diverse workshops and facilities: “Holland is further along on the road to implement the SDGs on a school strategic level. This will be the next step in Denmark. In Spain it is now mandatory to include the SDGs, which will have a huge impact. But it is still very much up to the local teacher to decide on how this is done. Italy is not as far yet – here it is very much up to the local teacher to decide if and how the SDGs should be included in the teaching and training”.

On the same line Italy states: “All the countries involved in this project are working on Bioclimatic Design and sustainable building materials. Obviously in some countries such as those in Northern Europe it is much more common to see cities houses buildings constructed in this way, it depends a lot on national legislation and how various governments push in this direction”.

Also Spain underlines some differencies: “Among the differences, we were aware of the development of timber construction in Germany, especially through Passivhaus certification. Thanks to the project we have seen that in Denmark, above all, and it seems that this is also extensible to the Netherlands (Koning Willem I building, that one with zero emissions) the construction solution with wood is quite developed. In Spain there are signs that this sector is on the way to develop wood construction with the creation of several CLT manufacturing companies.”

It is felt as a great value to understand these differencies among countries, this could only be the criterion that can generate and allow a growth: becoming aware of the steps that need to be taken for an improvement of any dimension could only come from a comparison.

Also, as said, the difference is felt with regard to the national regulations about the general construction sector: “The different building regulations also have an impact on this. In some countries the building regulations are becoming really strict regarding sustainability. This will definitely have an impact on the teaching and training in the VET-schools – and will motivate the use of the SDGs”.

And again on the building processes related to the ducation system in general: “There is a big difference between the countries regarding how the build and construct – obviously. And the schools have very different workshops and facilities. Holland is further along on the road to implement the SDGs on a school strategic level. This will be the next step in Denmark. In Spain it is now mandatory to include the SDGs, which will have a huge impact. But it is still very much up to the local teacher to decide on how this is done. Italy is not as far yet – here it is very much up to the local teacher to decide if and how the SDGs should be included in the teaching and training. A big difference also is, that in Denmark children learn about the SDGs in the primary school on every level. This means that we need to plan our teaching and training in this perspective.”

Still on education another difference is felt: “A big difference also is, that in Denmark children learn about the SDGs in the primary school on every level. This means that we need to plan our teaching and training in this perspective”. So the project has been felt to have given to the school partner in Denmark a new perspective on what the next step should be in terms of including the SDGs in a broader sense in education and more strategically.

On the same wavelenght as Denmark even though strating from another perspective Spain states: “As of today, webinars are the materials generated that are most highly valued by students and teachers. They are a didactic and inspiring tool that can be used in a cross-cutting way to talk about sustainability in other branches of VET, particularly in construction.” The project created, once more, new perspectives: “The rest of the materials generated, we believe that many of them are also inspiring and constitute a first step in the teaching activity in training cycles in the professional family of Building and Civil Engineering. This applies, in particular, to CIFP Someso. Our materials, in fact, have been agreed with the students and had, from the beginning, their approval. Our intention is to use those that best suit our circumstances and that we consider most attractive. To this end, at the beginning of the next academic year, an internal dissemination day will be held among the members of the department.During the dissemination days we have noticed an interest of the part of the teaching staff of this family in accessing information about these materials as well as the materials themselves.”

With regard to the motivation, that needs to be taken as point of reference when it comes to speak about teaching sustainability, a difference is felt also on the teaching methods used across the Eu countries: “There is a difference in how we motivate the use of SDGs. In Spain it is top-down (it is mandatory), and in Holland and Denmark it is more bottom up. We believe that the right way would be to do both. In Denmark we need to address the SDGs in a more strategic manor – or else we risk that only some teachers implement them in their teaching and training” so good suggestions came from the confrontations and activities created within the project.

The project and the interactions between partners generated new insight also for those countries which are ahead in terms of encompassing suatinability in the shool curricula in fact. “We made new partnerships, and we learned a lot about other school systems. Through this project we have gained new perspectives on how to implement SDGs in our teaching and training. But the two most important learnings for our part is:

- We need to address the heart/feelings more when we plan our teaching and training if we want to make lasting changes.

- We need to address the SDGs in a more strategic way as a school”.

Thanks to the project activities in Spain there is a new feeling about improving the attention to sustainability: “Ideally, sustainability should be worked on as a cross-cutting issue that is not restricted only to something academic, that is, to try to imbue students with its importance and to contemplate it in all the activities they carry out, both in and outside the educational centre.

Nowadays, in CIFP Someso we are far from that. The reasons are very diverse, but a key one is the lack of material resources (teachers involved in projects don’t get a reduction of lessons, for instance) as well as the apathy of the students, very little given to getting involved in dynamics outside the purely academic ones.

In Spain, sustainability was not included in any VET curriculum. It is clear that a commitment is needed at state level, on the part of the government and educational institutions, so that it is taken into account in educational centres and is not something secondary or ancillary. In the next academic year, with the new VET law, a professional module on sustainability will be included in the curriculum of all training cycles. This is the first step in this direction. The SDGs will be dealt with in this module”.

Future on sustainability: a common point of view about teaching sustainability across the EU

With regard to both motivation for students, teaching SDGs and the support that institutions have to give to teachers about encompassing sustainability in school curricula, a diffrence is felt bewteen Southern countries and Northen countries, in fact partners from Spain state: “We are all aware that a shift is needed to include sustainability in education and to emphasise the sustainable development of the planet. Awareness-raising is the way forward and should start at early stages of learning. This work must have a generalist approach, i.e. it does not depend solely on individual teacher initiatives. Support from educational institutions is needed”.

Generally speaking, the differences between countries about all the dimensions related to sustainability and especially to the relation sustainability-school-quality of teaching is felt as linked to the general setting of the national education systems: “At the present time, Netherlands and Denmark are much more advanced in the implementation of sustainability, SDGs for example, at all educational levels”, this is therefore to be addressed to “the differences between the educational systems: the figure of the specialised workshop teacher in Europe is still present, for example, bricklayers, while in Spain VET teachers have a university degree. This fact penalises the quality of teaching. Educational resources and the involvement of companies in Danish and Dutch VET is much better than in Italy and Spain.”

Also the the recruitment of teachers is acknowledged to be very different and this has an impact on the quality of teaching. Common perceptions come from Italy and Spain: “First, the main difference is related to our education systems. In italy, we have a public education system that complements vocational training schools (VET). In the other partner countries, the education system is very lean, dynamo, allows students after the first years of common education to make an informed choice whether to continue in vocational education and then specialize or to continue their education that will lead them to university.”

Despite the various differencies registered from Greenwave partners among their home countries on all levels and dimensions in which sustainability is related to education, schools, institutions and quality of teaching as well as technical features/processes about building and construction works, commonalities are reported with regard to the future about sustainability: “In our particular case, we were certainly not aware of the approaches to sustainability followed by our Danish and Dutch partners. Our knowledge of sustainability was very basic and generic. Now that we have implemented this project, our awareness of sustainability has increased significantly and, thanks to what we have experienced and observed, as well as the materials generated, we have a starting point for this. The materials developed in the project will be used in the teaching activities of some modules of Building and Civil Engineering.We hope that there will be future projects related to this topic in future Erasmus+ calls.” The contributions that the Greenwave project made for each country is felt to be relevant and so future perspectives on other projects similar to Greenwave in Vet are desidered.

Is also felt as a common point the moving forward of Eu in the same direction: “Among the common points, it was noted that, although each country has its own specific building regulations, there is a tendency to unify towards a European standard in terms of contents and minimum requirements” Spain notes.

Beside Spain, also Italy states: “We learned to better understand the various stages of evolution of a European project, and to compare ourselves with the different educational models of the partner countries. The Green Wave Project has been extremely important for our vocational school, we have had the opportunity to strengthen European identity and active citizenship and to participate firsthand in the various stages of carrying out the work planned for each Project Result. From a work point of view this meant added value in terms of improved skills and from an educational point of view a plus for the staff, faculty and students”.

PART III

ENVISIONING THE FUTURE ABOUT SUSTAINABILITY:

teachers’s and students’ point of view on sustainability

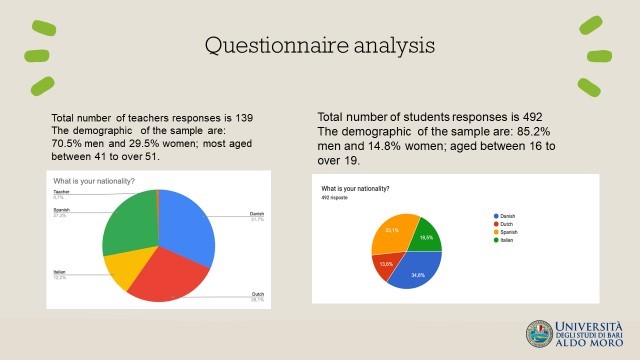

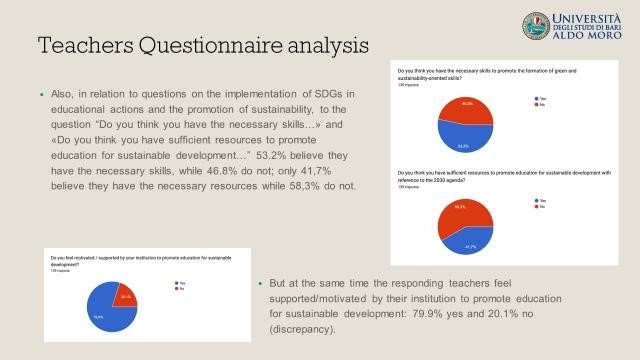

Here are the results of the first questionnaire administered to teachers and students involved in the project: the analisys showed, as said, a strong need of education about sustainability.

The result of the second questionnaire will follow to make a comparison and a final evaluation and impact of the Greenwave project. Is it possible to understand the vision of the futeure on the teachers’point of view by comparing the answers given in the two questionnaires administered.

For the students’ point of view we will compare the results of the first questionnaire with the final interviews to 16 students as requested by Result 6 of the project.

• TEACHERS’POINT OF VIEW ABOUT SUSTAINABILITY

FIRST TEACHERS’QUESTIONNAIRE

The questionnaire intends to understand how VET contexts promote sustainable education and through which projects and actions.

Here follows the preliminary results of this survey, analyzing the teachers’ answers.

SECOND TEACHERS’QUESTIONNAIRE

COMPARISON BEFORE AND AFTER THE GREENWAVE PROJECT-CONSIDERATIONS ABOUT THE FUTURE: TEACHERS’POINT OF VIEW

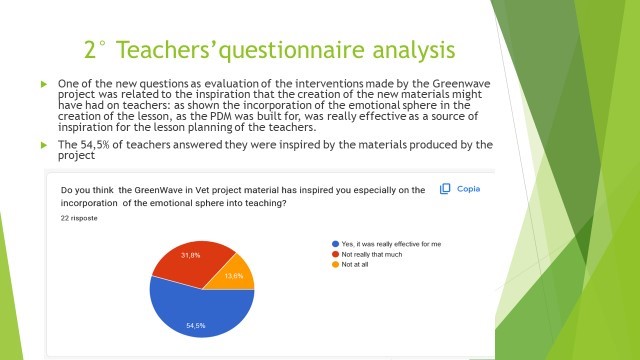

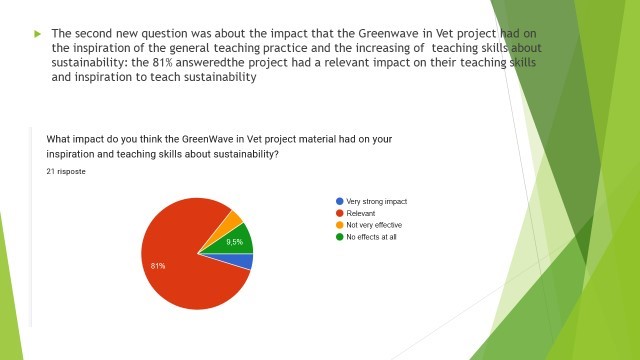

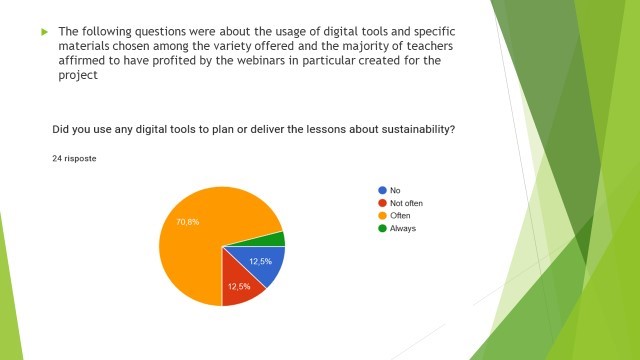

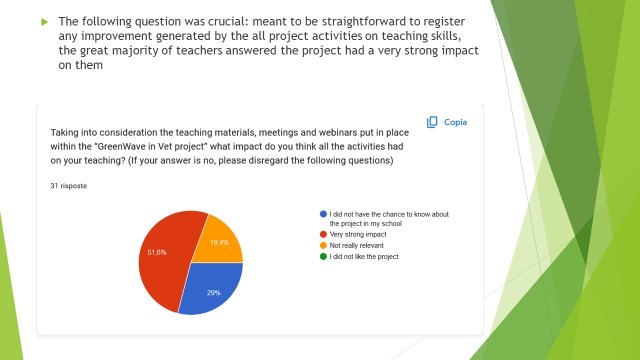

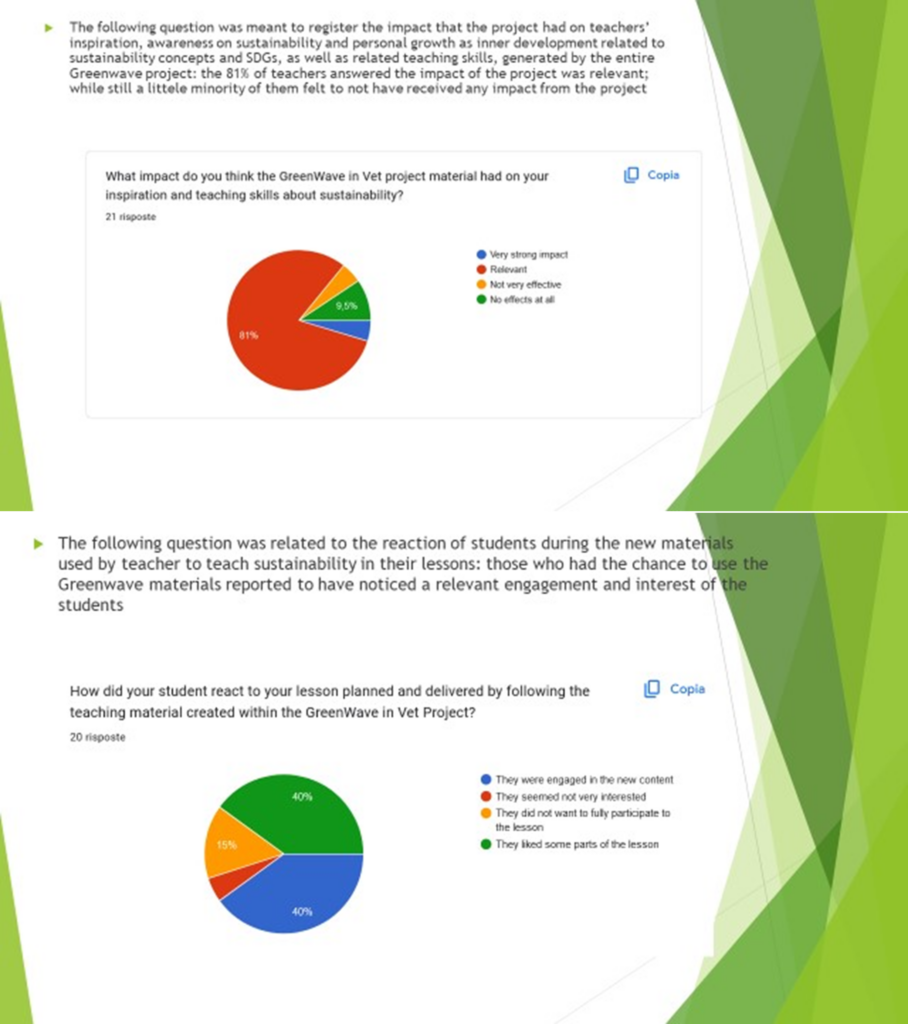

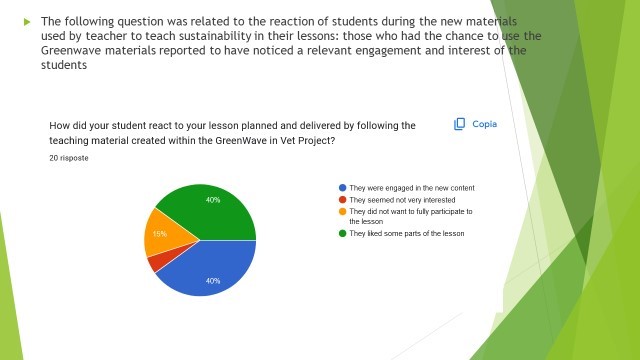

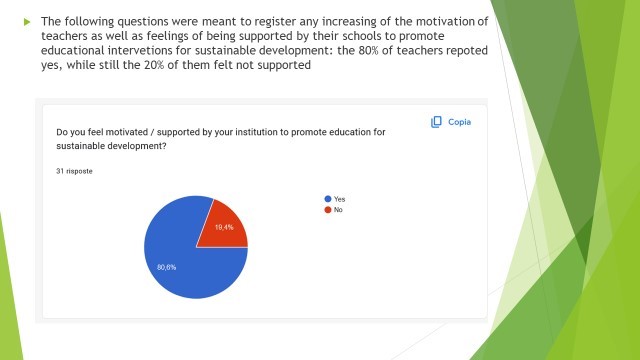

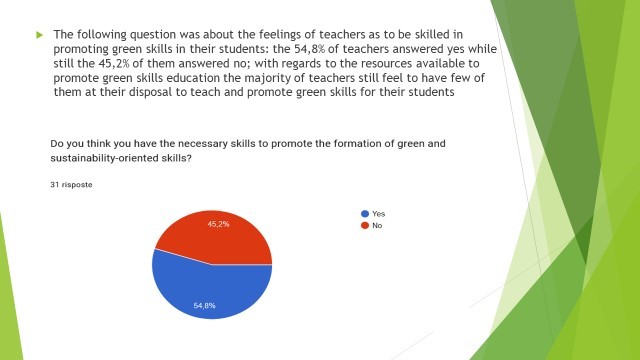

As it is clear from the graphs shown, it is possible to grasp the impact of Greenwave in Vet project had on the teachers involved: generally speaking, although not all the teachers belonging to the schools which were partners of the project, took actively part in the Greenwave project activities, those who had the chance to participate show a relevant increase both on their personal growth and inner development about the awereness on sustainability as well as inspiration and on practical teaching skill related to sustainability and SDGs incorporation in the lessons.

In line with the perceptions of the people and professionals involved in the project as partners who actively participated and created the entire project activities, the teachers involved could affirm that the whole Greenwave in Vet project had a strong impact on them on variuos levels and dimensions.

Still much more needs to be done on sustainability, as the teachers who answered the questionnaires witnessed, on the boosting of the awereness of what is sustainability, what are the green skills, what and how needs to be incorporated in the curricular lessons, but it can be said the educational interventions such as the Greenwave in Vet project really can work, increase, foster and boost the general awareness and specific skills about sustainability and sustainable development.

- STUDENTS’ POINT OF VIEW ABOUT SUSTAINABILITY

FIRST STUDENTS’ QUESTIONNAIRE

SECOND STUDENTS’ QUESTIONNAIRE

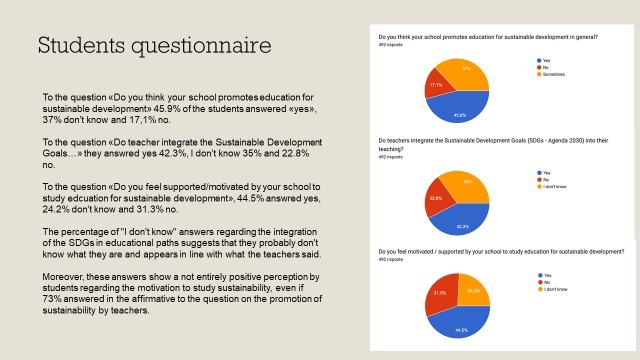

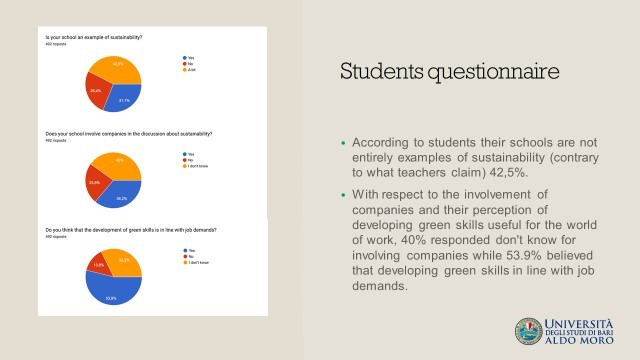

The most important points to be highlighted that emerged from the students’answers to the first survey are

- Poor knowledge of the concept of sustainability and above all of the objectives of the 2030 agenda (quite in line with what was highlighted by the teachers)

- A not entirely positive perception of the promotion of sustainability at school and by the school

After the educational activities promoted by the entire Greenwave in Vet project the students (two students interviewed from each partner) were asked the following questions:

1-To what extend the “Greenwave in Vet project” has inspired you about studying sustainability?

- Which impact do you think the “Greenwave in Vet project” will have in the next future at your school?

- What did you like the most about the project? Why?

Here follows a summary of all the interviews made to the students belonging to the partners’schools from each country at the end of the school year.

The students from Danmark from the two parters’schools both said, that they were very inspired by the new materials presented to them from the teachers: materials made from wood, grasses, seaweed, recycled plastic. The materials are used to construct houses in a new and more sustainable way instead of using glass wool; they also thought that their teachers have got new insights in sustainability – and the importance of working with sustainability.

They said to have liked the way their teacher challenged them to think in a sustainable way because they had to be inventive, use their brain and skills in a new and different way.

On the same wavelenght, students from Spain reported:

“Until now, all the projects I have done in my school have used concrete and steel. Thanks to the Green wave project, now I consider designing houses with a wooden structure.”

“I was not aware of the potential of wood in Galicia and thanks to this project I have discovered that we have a great wealth that can be used to build much more sustainable and healthy houses”.

With regard to the materials used within the lessons:

“According to the teachers, some of the materials developed in this project will be used in the next school year”.

“ Some of the materials elaborated in this project will be used in the next school year based on the new curricula since there will be a new subject on sustainability”.

About what they liked the most and why about the project they reported:

“This project has made me ask myself what I can contribute to sustainability when I leave school and start to work in a company.”

“The webinars that were created during the project. I find them very intuitive and educational. It brings up materials that I was completely unaware of.”

Students from Netherlands reported:

After a number of guest lectures about sustainability, nature inclusive, bio-based construction, it got me thinking. The guest lecture from Global Goals put me to work, so I started reading about the global goals and looking at what best suits our home. After the guest lesson on materials, I was also completely taken into the best choices, so I discovered that hemp is a good insulation because it grows back, he showed us a type of glass that I have never seen before. By bringing samples he took the whole class with him and I was quickly interested.

The global goals have inspired us to conduct research into sustainability. This had a major impact on our research as we knew what to pay attention to. Some of the things we have done research into are nature inclusivity, bio-based construction and sustainable construction. Consider the global goals of ‘life on land’, ‘sustainable cities and communities’ and ‘affordable and clean energy’.

With regard to the perception of the impact that the project had on them, they said:

Everything becomes more sustainable, more environmentally friendly and better for the future. Our school already has solar panels and sustainable materials and much more could be added in the future. In this way they pass on to the students that sustainability is important for this generation. If we all do more research into sustainability with the entire new generation and contribute, we will keep the planet alive for a little longer.”

“By giving a project about sustainability, nature-inclusive construction and bio-based construction, we ensure that we think more about sustainability in subsequent projects. This will ultimately ensure that we can make more sustainable choices on our own in the future that will ensure that the world becomes more sustainable piece by piece.”

The answers to the question about what did they like about the project and why they answered:

“How much I have learned about sustainability, biobased, nature inclusive and environmental friendliness. The research into different materials that are best to choose, such as hemp insulation, etc. I also really enjoyed designing the house, sketching it in broad outline and working it out later. I also really liked the model and material board because you were really working with your hands.” “The principle that we had a ‘real client’ has ensured that we have less difficulty in this in the future. I also liked the creativity we could use in designing a sustainable dream home.I only now realize that all this information is important for the future, after doing all this research I am very happy with the knowledge I now have. With this I can contribute to a better world for our generation.”

Other two students interviewed from Netherlands about being more aware of sustainability issues, materials, techniques thanks to the Greenwave in Vet project said:

“We have noticed more attention on sustainability at school…we have been very busy especially this year: we worked on a project about building a small house with different materials and we learnt a lot about alternative materials, insulations, transports”

“Yes, I think we will be able to use them in the future! That’s a good thing!”

With regard to the feelings and impressions of the two students about the impact that the project could have in the next future they reported:

“Students will look differently at the materials to use when building…I learnt how to give to materials a second life.. I will do it!”

“Yes, I think in the future it will impact everyone, it will be more common to used alternative materials, different heating systems..; also it is important for your own house!”

About the learning, the improvement of learning on sustainability thanks to the aim of the project which was embedding sustainability in the whole school curricula not only proposing isolated projects or thematic sessions about it- the students said:

“We have been discussing a lot during the year about sustainability.. people get bored if you work on a single project..while discussing almost everyday made it very intersting!”

“Discussing continuously during every lesson has helped a lot… we learnt a lot how to used biobased materials!!”

The enthusiasm of the students while reporting their perceptions about their learning thanks to the project carried out during the year was great!

Students from Italy responded:

“The thing I enjoyed most having addressed sustainability issues related to materials, new construction techniques having talked about it with my teachers”.

“It was very interesting to talk about what we can do to improve environmental sustainability in construction and new techniques, and to have European inspiration on what are the construction techniques in northern Europe”.

About the impact that “Greenwave in Vet project” will have in the next future at your school, they answered:

“I believe that my school will invest time in sharing the results of the project and the work done with the next classes, it will certainly be an inspiration for future teaching models”

“This project has been very inspiring for our school, has allowed us to compare ourselves with other teaching models, and will surely enable us to improve our European dimension for the future. Certainly the project has strengthened the green wave in us students, this is a topic that is very much felt in Italy” At the end, about what they liked the most about the project they said:

“I really enjoyed watching the webinars and seeing what other European countries are doing to maximize sustainability in their buildings, through these webinars we were able to learn more about and evaluate the impact of other building techniques on our environment. At school we study construction techniques, the use of environmentally sustainable materials, we have the opportunity to participate in seminars with leading companies in the field of sustainable materials”.

“The webinars have allowed for more interactive and certainly very interesting lessons”.

FINAL CONSIDERATIONS

The Greenwave in Vet project has been a journey.

A journey of learning for all the people involved in it. An inspirational movement has accompanied the whole project, starting from the partners going through the teachers and students with all the people encountered on the way.

The issue of sustainability has shown an amazing power of transformation: when put on the table, with all the educational intervention that have been created and put in place within this project, sustainability can really inspire people of any age and push them to act for the good of the whole community.

The core of the project has been felt as education: because is precisely education that bonds generations together.

The educational relashionship, which is the focus of the rapport between teachers and students, is the vehicle through which sustainability can be conveyed, perhaps in the best way beside the others.

Coming to know better all the dimensions in which sustainibility is being studied and acted, thanks to all the activities required by the Greenwave in Vet project, for the partners, teachers, students who have been the actively participants of the same project, has brought a new level of awareness, inspiration, desire to act for the good of our planet and people.